Regarding the issue of “AI taking people’s jobs. I read about an interesting example in a book where the invention of a machine that was supposed to greatly simplify people’s work ultimately led to worsening working and living conditions for laborers (and, incidentally, the British occupation of Egypt). It’s about Whitney’s machine, which simplified cotton processing.

Before the invention of the loom, fabric was worth its weight in gold. Literally, a gram of silk cost almost as much as a gram of gold. Stories about crime in the 18th and 19th centuries are almost always about how criminals were put in jail or sent to Australia for stealing a handkerchief, a bundle of lace, or some other seemingly trivial item, but in reality, these were often items of enormous value. A pair of silk stockings could cost 5 pounds, and a bundle of lace could be sold for 20 pounds — enough to live on for a couple of years, and a very serious loss for any shop owner. A silk cloak cost 50 pounds sterling, which was unaffordable for anyone but the highest nobility.

John Kay, a young man from Lancashire, invented the mechanical (flying) shuttle — one of the first revolutionary inventions necessary for the development of the textile industry. Kay’s mobile shuttle doubled the speed of weaving work. Spinners, who were already struggling to keep up with weavers, fell even further behind, and problems began to arise across the entire supply chain, creating huge economic difficulties for all participants in the process.

In 1764, an illiterate weaver from Lancashire named James Hargreaves invented an amazingly simple device known as the “spinning jenny, which used multiple spindles to do the work of ten spinners.

Before this invention, home craftsmen spun 500,000 pounds of cotton by hand each year in England. By 1785, thanks to Hargreaves’ machine and its improved versions, this number had jumped to 16 million pounds.

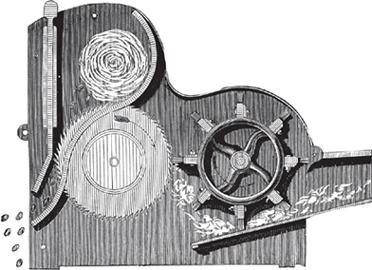

In England. In the USA, there was a different problem. In the American South, the only type that grew well was short-staple cotton. But it was not profitable to harvest because each boll contained sticky seeds – three pounds of seeds for every pound of fiber, and they had to be picked out by hand. This was so labor-intensive that even using slave labor didn’t pay off. By hand, one worker could only clean about 1 pound (0.45 kg) of cotton per day. Eli Whitney solved the problem by inventing a simple rotating drum, which used nails to grasp the fiber, leaving the seeds behind. He called his machine a “gin” (from engine). Whitney’s machine allowed one person to clean up to 50 pounds (about 22.7 kg) of cotton per day. That is, 50 times more. In effect, it replaced 50 people with one.

At that point, slavery existed in six states in the US; by the time of the Civil War, it had spread to 15.

Why? It turned out that instead of reducing the need for labor, Whitney’s machine increased it: because cleaning was no longer the bottleneck of production, more workers were needed for planting, harvesting, and processing the increasing crop. The US became the main global supplier of cotton, which made the textile industry in Europe (especially Britain) dependent on American raw materials. This led to the growth of the slaveholding system in the southern states, and in England, increased the share of child labor in production (because they didn’t need to be paid, just fed, and children managed better).

Subsequently, when the Civil War in the US ended, cotton prices fell, leading Egypt (where high-quality long-staple cotton was grown and sold to England) into an economic crisis and a rise in foreign debts. Eventually, this was one of the reasons for the British occupation of Egypt in 1882.

Returning to the topic of AI. The job market adapts, but sometimes slowly and with losses. In the long run, new jobs will appear, but the transition period might be accompanied by mass unemployment and social upheavals.

Indeed, there is still no such thing as true artificial intelligence. AI will become real AI when it understands and utilizes knowledge about the structure of the world, not just projections of this knowledge. Take image generation—it uses “projections—a database of annotated photo and video materials. It does not use knowledge about anatomy and the structure of the world. The same is true in GenAI—projections are everywhere, not pure knowledge. It seems that the current breakthroughs in GenAI are unsuitable for storing, accumulating, and using “pure knowledge.

Also, we need not just a system that can correctly answer our trivial questions. We need a system capable of posing the right non-trivial questions. Large language models (LLM) by their nature are not capable of this.

Nevertheless, the stories of the inventions by Kay, Hargreaves, and Whitney do draw parallels.