To diversify the collection of contemporary artists with the most compelling pieces, let’s turn to a well-known figure: Vasily Vereshchagin.

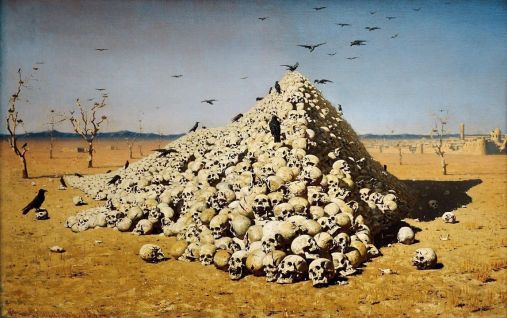

The first painting is “The Apotheosis of War, one of his most striking works. My research suggests that, contrary to its common interpretation as an anti-war manifesto—widely accepted by sources like Wikipedia—it wasn’t intended as such. Instead, the painting belongs to the “Barbarians cycle, depicting the brutality of Samarkand’s rulers and implicitly supporting Russian expansion in Central Asia.

Vereshchagin exhibited his Turkestan Series at the Crystal Palace in London. According to the English Digital Humanities Institute and several other sources, his introduction to the exhibition catalogue framed Russia’s conquest of Central Asia as a necessary civilizing mission. It was also intended to allay British doubts about who their true friends and neighbors in the region were.

Another work from the “Barbarians cycle is “Surrounded—Pursued (1872), which the artist himself later destroyed by burning it.

Vereshchagin wrote, “Whatever the cost, with full respect for law and justice, the question [of colonizing Turkestan] must be resolved without delay. This concerns not only Russia’s future in Asia, but above all the welfare of those under our rule. Frankly, they stand to benefit more from the final establishment of our authority than from a return to the old tyranny…

It seems the series was funded by Konstantin Kaufman, who oversaw the conquest and colonization of Central Asia. While I couldn’t confirm this directly, some sources suggest that the goal of exhibiting these paintings in London was to convince the British of the necessity of Russian control over Samarkand. The show, reportedly, had political undertones, aligning with ongoing negotiations over spheres of influence in the region.

Thus, while later interpretations of “The Apotheosis of War cast it as an anti-war statement, the painting originally served as a propaganda tool, reflecting the historical conflicts and imperial interests of Russia.

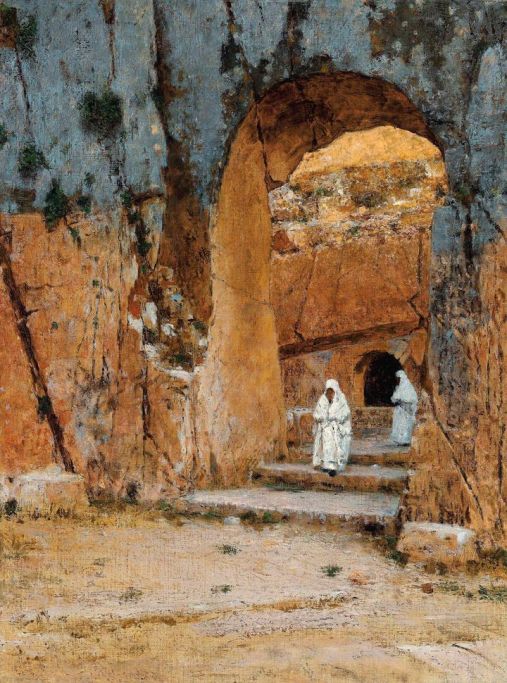

The second painting, featuring an eagle, is titled “Russian Camp in Turkestan.

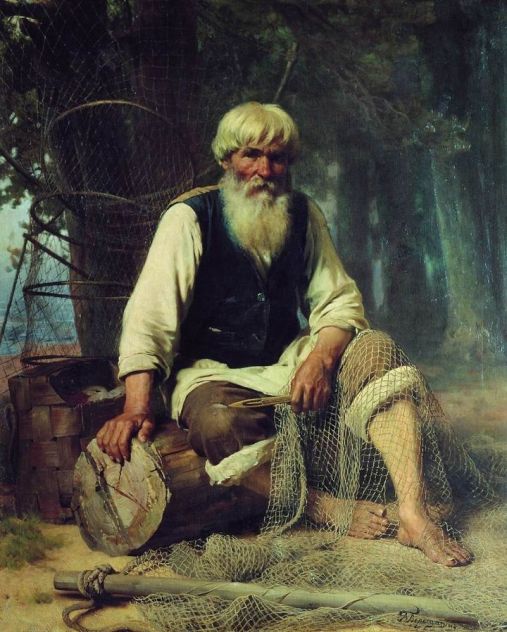

In many ways, Vereshchagin resembles a photojournalist of his time—only instead of a camera, he wielded brushes, canvases, and paints.

Similar posts are grouped under the tag #artrauflikes, and the complete collection of all 121 entries can be found on beinginamerica.com under the “Art Rauf Likes section—unlike Facebook, which neglects nearly half of them