Curiosities — four items on various topics: about face patches, wigs, an architect, and milk sickness.

First: I’m reading that in England, during the 16th to 18th centuries, it was fashionable to wear artificial beauty marks, known as mouches (French for ‘fly’). Eventually, these beauty marks took on shapes like stars or crescents, worn on the face, neck, and shoulders. It is written that one lady had a carriage and six horses galloping across her cheeks. At the height of this fashion, people wore a multitude of mouches, probably looking as if they were swarmed by flies.

Interestingly, both men and women wore mouches, and they were reckoned to reflect a person’s political leanings depending on which cheek they were worn – on the right (by the Whigs) or on the left (by the Tories). Similarly, a heart on the right cheek meant that a person was married, and on the left, that they were engaged. They became so complex and varied that they spawned an entire vocabulary: on the chin called silencieuse, on the nose – l’impudente or l’effrontée, in the middle of the forehead – majestueuse, and so on throughout the head. In the 1780s, artificial eyebrows made of mouse skin briefly became fashionable.

Thus, stylized stickers and acne patches in the shape of stars and hearts are a modern counterpart to this trend. We await the modern equivalent of mouse-skin eyebrows.

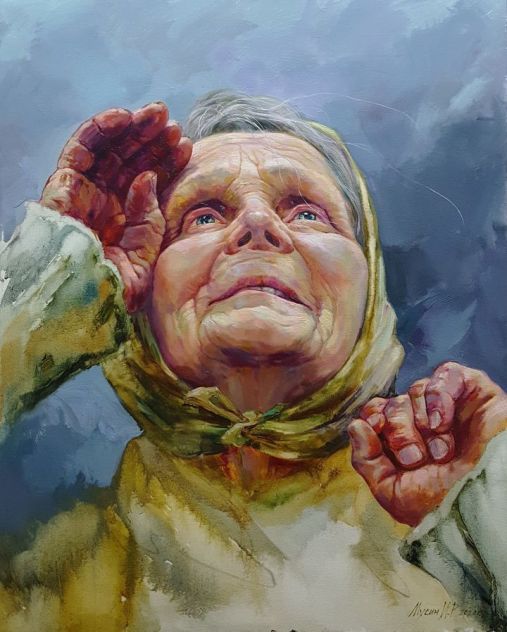

Illustration: “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760. The text below – “these artificial spots add ‘vivacity’ to the eyes and face. However, placed poorly, they could mar beauty.”

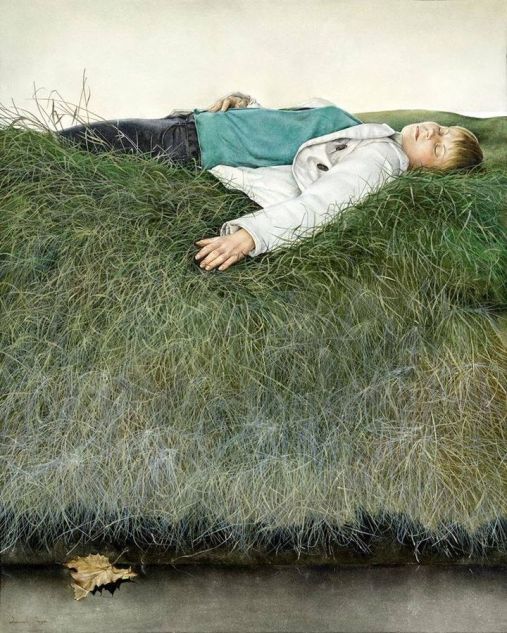

Second: It turns out that there was a condition called Milk sickness in the USA. At the beginning of the 19th century, it claimed thousands of lives among settlers in the Midwest, especially around the Ohio River and its tributaries. The essence of it was that a seemingly healthy cow would start giving milk that could quickly “knock one off their feet” in the worst case, or just cause severe suffering from vomiting and pain if you were luckier. The culprit was a plant the cow ate, known as white snakeroot, but, of course, no one told it what was safe and what was not. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby is credited with figuring out the cause. She was told about it by a Shawnee woman she had befriended, after which Bixby conducted experiments to observe and document evidence.

Bonus curiosity about Benjamin Latrobe, the architect of the Capitol in our Washington. Finished college, tried building something in Europe, didn’t work out, his wife died, went bankrupt, the guy decided to drop everything and move to the States. Met Washington’s nephew and the rest is history. Seven years after moving, he was already building the Capitol, and before that, he designed several other important buildings today (Philadelphia Bank, original jail in Richmond, etc.). Basically, networking — it’s important, and it’s crucial in moments when things just aren’t going right to just take everything and change it.

About wigs, it’s even more interesting. From the mid-17th to the early 19th centuries, men wore wigs so massively that the fashion lasted a whole 150 years. Wigs were made of anything: human and horse hair, silk, goat wool, cotton thread, and even wire. They were very expensive — up to 50 sterling pounds each — and were considered such valuable property that they were bequeathed by inheritance. The bigger and heavier the wig, the higher the status of its owner — hence the expression ‘bigwig.’ Since wigs were often stolen, they were the first things robbers grabbed.

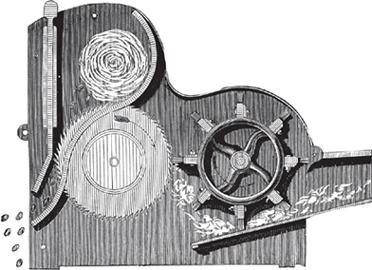

Wig maintenance was also a hassle. Once a week they were sent back for “rebaking” to re-curl the locks — this process was called fluxing. From the 1700s it became fashionable to sprinkle the wig with white flour daily (incidentally, “to sprinkle one’s head with ashes isn’t about this. It’s from the Bible, used as a symbol of repentance, mourning, and admission of guilt). When a wheat shortage hit France in the 1770s, it triggered massive riots — people were outraged that scarce flour was being used on aristocrats’ heads instead of bread. By the end of the 18th century, colored powders, especially blue and pink, became popular. The powdering process was a whole ceremony: they put on the wig, covered the shoulders with cloth, put the face in a paper funnel (so as not to suffocate), and a servant would spray powder on the head using bellows.

Some aristocrats took style to the next level: one prince hired four servants to simultaneously spray different colored powders, through which he dramatically walked. Lord Effingham kept a whole five French masters just to care for his hairstyle.

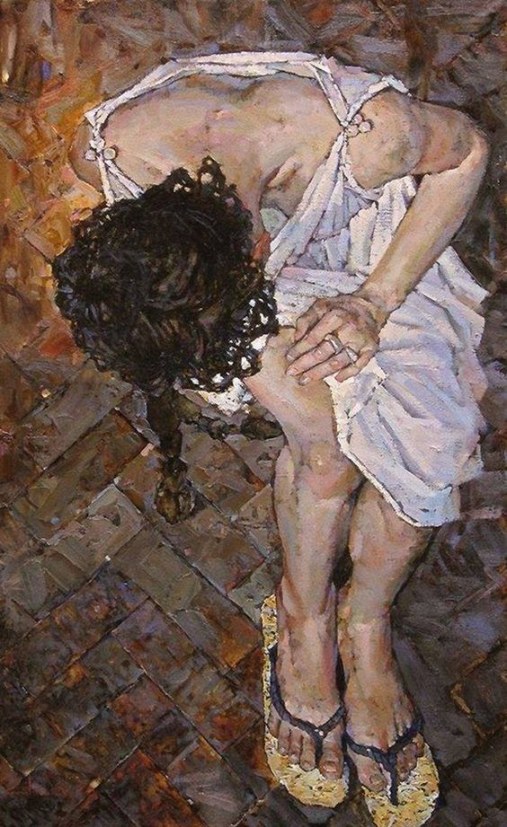

By the way, women’s hairstyles were not that simple either. They were built on a wire frame, and for volume, they added wool and horsehair. The height of some women’s hairstyles reached 75 centimeters, so that the ladies barely fit in carriages and sometimes had to ride sticking their heads out the window. There were even instances when hairstyles caught fire from chandeliers, sometimes ending tragically. Of course, the hairstyle wasn’t dismantled for months, maintaining its shape with paste, and to avoid disrupting the structure during sleep, they slept on special wooden supports. Notably, there were significant hygiene issues: the hair was teeming with insects, and one lady even lost a child after discovering a mouse nest in her hairstyle in the morning, having been deeply shocked.

But the fashion for wigs among men sharply ended at the beginning of the 19th century. So much so that desperate wigmakers petitioned King George III to make wearing wigs obligatory. But the king refused. Old wigs were then used as household rags. Today, wigs are still worn in British courts — they still wear horsehair wigs, costing about 600 pounds, which are customarily soaked in tea to give them an old-fashioned look — after all, a too-new wig might give away an inexperienced lawyer.

All this — for the sake of fashion!