This is an excerpt from the poem “Square” by English poet James Clifford, translated by Vladimir Livshits. Clifford was a man with a remarkable destiny, crushed in the vices of two world wars. He was born on the eve of World War I, in 1913 in London, and died in 1944 while repelling a German tank attack in the Ardennes.

Paradoxically, the legacy of the young English poet was better known in the Soviet Union than in his homeland. While in England they asked, “Who is Mr. Clifford?”—in the USSR, his new poems were regularly published from the mid-sixties onward. Thanks must be given to his translator—Vladimir Livshits. He was the first to translate into Russian the famous, seemingly familiar lines from “Retreat in the Ardennes”: “There were five of us left. In a chilly dugout. The command had lost its mind. And was already fleeing.”

But Livshits didn’t just translate these lines; he practically “sanctified” them, because James Clifford, the young English poet who fell in 1944 while repelling the German attack, was for Livshits not just a translation subject but also his own creation. The real James Clifford, who supposedly was born in London, lost his parents early, and was raised by a grandfather—a connoisseur of English and Scottish folklore—never actually existed. Following Walter, Livshits repeated: “If Clifford did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.” And he invented him.

For decades, Livshits published his own poems in the Soviet Union, presenting them as translations of the non-existent English poet James Clifford.

(taken from the video “Armen and Fedor,” “Comrade Hemingway: How the USSR reforged the novel ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’?”)

This is how you hack the system 🙂

* * *

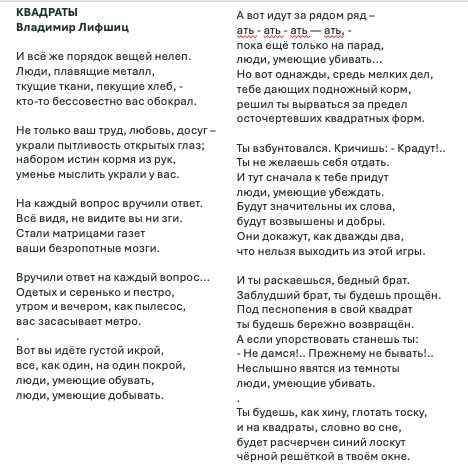

SQUARES

Vladimir Lifshits

.

And yet the order of things is absurd.

People, melting metal,

weaving fabric, baking bread—

Someone has shamelessly robbed you.

.

Not just your labor, love, leisure—

They stole the curiosity of open eyes;

Feeding truths by handfuls,

They robbed you of the ability to think.

.

For every question, they handed an answer.

Seeing all, you see nothing at all.

Your unquestioning minds

Have become matrices of newspapers.

.

They have handed an answer for every question…

Dressed both drab and colorful,

Morning and evening, like a vacuum cleaner,

The metro swallows you up.

.

Here you go, dense as caviar,

All cut from the same cloth,

People who can shoe,

People who can procure.

.

And here they go, row upon row—

March – march – march — march,

So far only for parades,

People who can kill…

.

But one day, amidst the trivial affairs,

Feeding you crumbs,

You decided to break out

From the tiresome square forms.

.

You rebelled. You scream: “They steal!”—

You refuse to comply.

And first, those will come to you

Who know how to persuade.

.

Their words will carry weight,

They will be exalted and kind.

They will prove, as twice two,

That you cannot leave this game.

.

And you will repent, poor brother.

Misguided brother, you will be forgiven.

To chants, you’ll be gently returned

Back to your square.

.

And if you persist:

– I won’t give in!.. No going back!…

Silently, from the shadows

Will come those who know how to kill.

.

You will gulp your despair like henna,

And on squares, as if in a dream,

A blue patch will be lined

With a black grid in your window.